Historical context

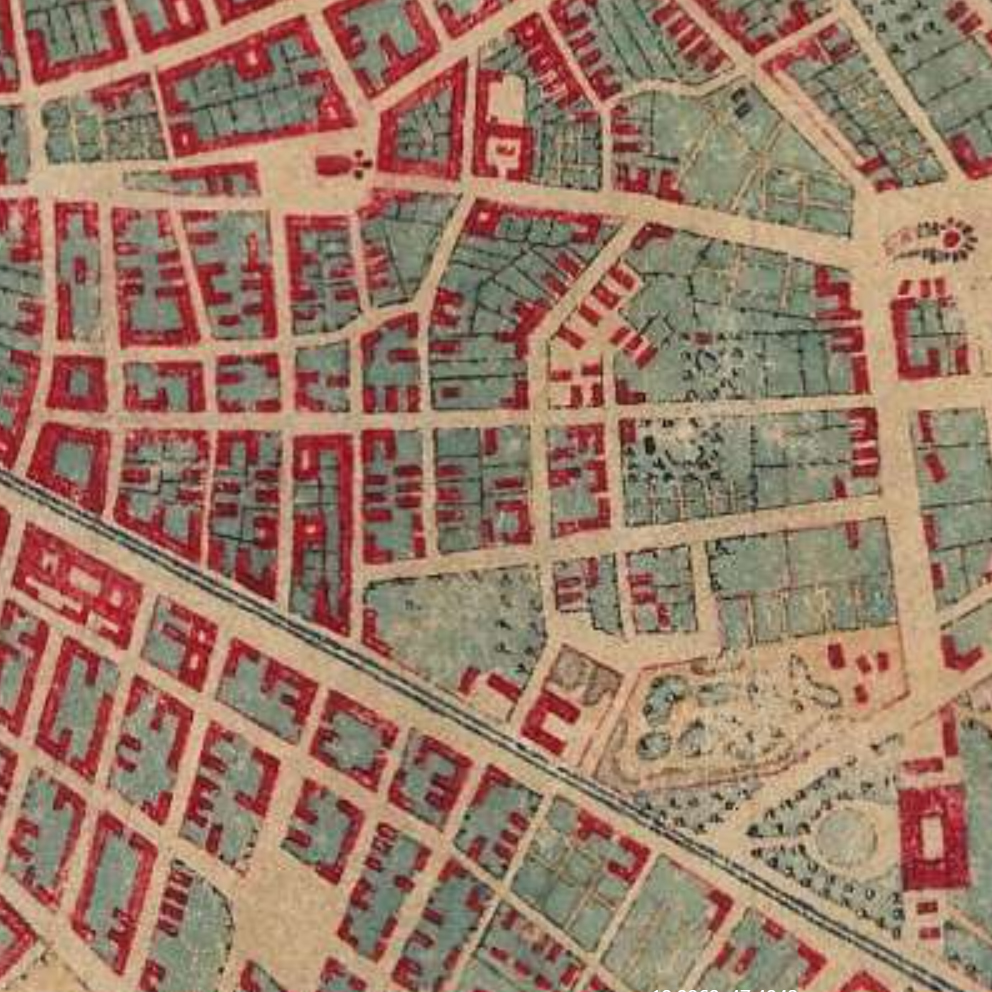

The first signs of the existence of Vienna come from the ancient Romain time. Romans set up a military camp named Vindobona in the first century . The camp has disappeared later, in the fifth century after the decline of the Romain Empire.

In 1150 the dukes of Bavaria decided to move his principal residence to Vienna. This step allowed Vienna to become a city for the first time. Another sign of the existence of Vienna during the middle age is the fortification wall built in 1200.

At the beginning of the 13th century, Vienna became an important part of a network of trade relations around the Danube. This trade networked used to follow the Danube route and and affected countries around it.

1 source : Stadt Wien Website, From the Roman Military Camp to the End of the First Millenary – History of Vienna, https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/overview/romans.html

In the 14th century a new architectural style appeared in vienna : Gothic style. The city was mostly refashioned with this with this imposing style. One example was the redesign of the church of St. Stephen’s or the Vienna Rathaus. The economy of the city was based the Danube trade but also on the wine growing. Wine growing is still a part of Viennese culture today.

Credit by : Juliette Vincens de Tapol

2 source : Stadt Wien Website, The late medieval Period – History of Vienna, https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/overview/romans.html

In the 15th century Vienna became the capital of the Holy Roman Empire and tand therefore the emperor’s seat and residence. As a consequence the building and architectural activity of the city was dominated by the viennese court and the church. The aristocratic families built their houses and palaces in Innerestadt but also in the suburbs influencing architecture and culture.

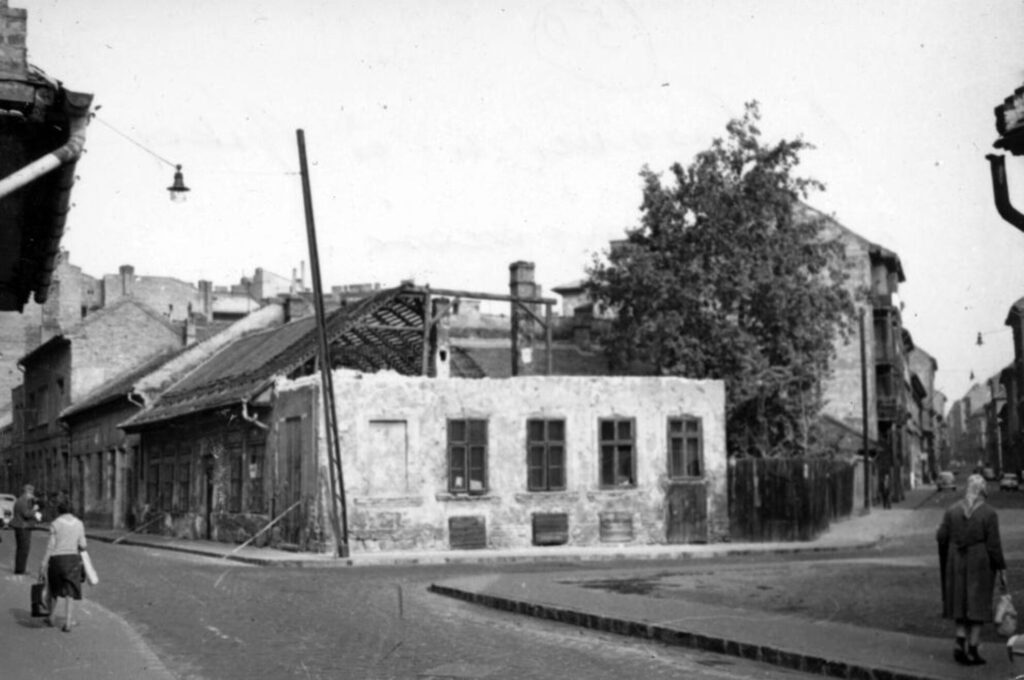

After the occupation of Napoleon Bonaparte between 1815 and 1848 Vienna’s infrastructures and building were not modern enough to go through the industrial revolution. This need of modernisation began more and more urgent.

“On the one hand, Vienna experienced an age of cultural excellence. On the other hand, the period was marked by the onset of rapid industrialisation combined with grave social problems.”

Quoted in Stadt Wien Website, Napoleonic wars to “Pre-March Period” – History of Vienna, https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/overview/romans.html

The city has also attempted to modernize on a European scale, for example by building meat markets to improve the city’s food supply, but these attempts have had similar difficulties.

In 1857, Emperor Franz Joseph had the city’s fortifications razed and instead built the “Ringstrasse”, a road encircling the city center, adapted to new transport means. This road welcomed the institutions of the new bourgeoisie. Buildings with a new style of architecture, historicism, have emerged: Museum, Opera House, Government Department but also Parliament building. This new architectural movement was notably led by the Austrian architect Otto Wagner. These luxurious and bourgeois modifications contributed to create a gap between the suburbs and the city center.

In the 19th century, a project had a major impact on the urban landscape and the morphology of the city : the regulation of the Danube, between 1869 and 1875. A new bed was created with the old branch of the city center, the “Danube Canal”. Merchant navigation was therefore carried out on the main river bypassing the city. These modifications allowed a great economic growth in the area between the Danube Canal and the main river.

3 source : Stadt Wien Website, The “Ringstrasse”-period – History of Vienna, https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/overview/romans.html

After the Second world war in 1945, more than 20 percent of the building stock was destroyed or largely damaged.

Between 1945 and 1955 the state launched major reconstruction projects in the city. These have had a great impact on urban development and the morphology of the city. The riverbanks of the Danube have been redesigned from scratch with modern designs. This project was the first major urban project since 1875.

4 source : Stadt Wien Website, The years of the Allied Forces in Vienna (1945 to 1955) – History of Vienna, https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/overview/reconstruction.html

After the Second World War, more and more attention was paid to the preservation of Vienna’s architectural and urban heritage. This resulted in the rehabilitation of densely built historic districts.

5 source : Stadt Wien Website, From the “Austrian State Treaty” (1955) to the European Union (1995) – History of Vienna, https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/overview/international.html

History of accessibility in Europe and Vienna

During the middle-age, disabled people are excluded from the society. People consider them unclean or a victim of the divine curse. Their disability provoked fear for most of the European population.

The Innere Stadt of Vienna was built between the middle age and 1850: it was therefore not designed to be accessible to disabled people and inclusive.

After the First World War, a system for the protection of disabled people was created in Europe. It covered only war veterans and war wounded because these people had “sacrificed for their country”.

After the Second World War, the condition of the handicapped evolved in Europe. Indeed, several millions of people came out of this war injured and disabled, and not only soldiers.

Since that time, organizations and associations have been working to improve social rights and support the disabled in Austria. After the 1970s, a new movement emerged calling for the implementation of human rights for people with disabilities: the SELBSTBESTIMT LEBEN BEWEGUNG.

Today the Vienna’s government try to make the city more accessible and inclusive. The historic center is still a complex place because it is part of the national heritage, an architecture protected by the government as said before. Transformations are therefore complicated.

6 source : Universität Wien Website, History of the disability movement in Austria, June 2018, https://lehrerinnenbildung.univie.ac.at/en/fields-of-work/inclusive-education/research-projects/current-projects/history-of-the-disability-movement-in-austria/

On site

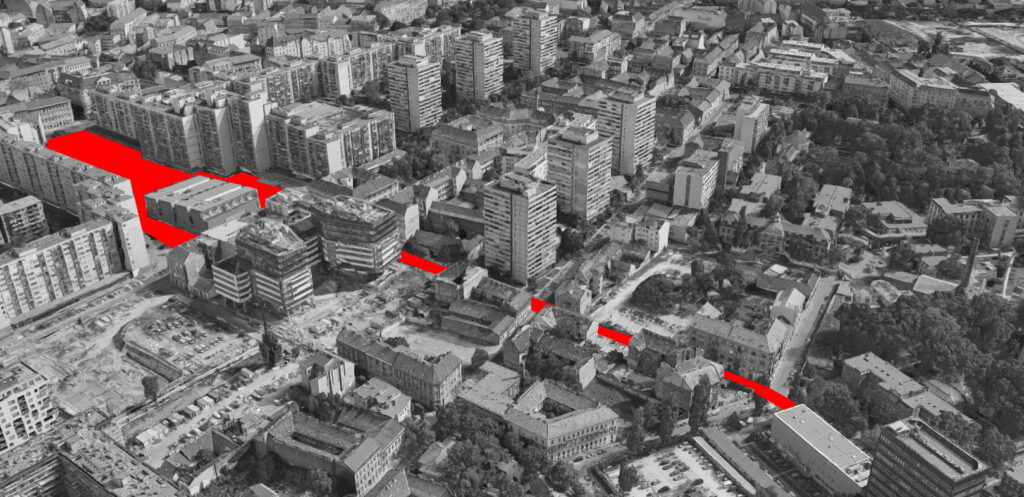

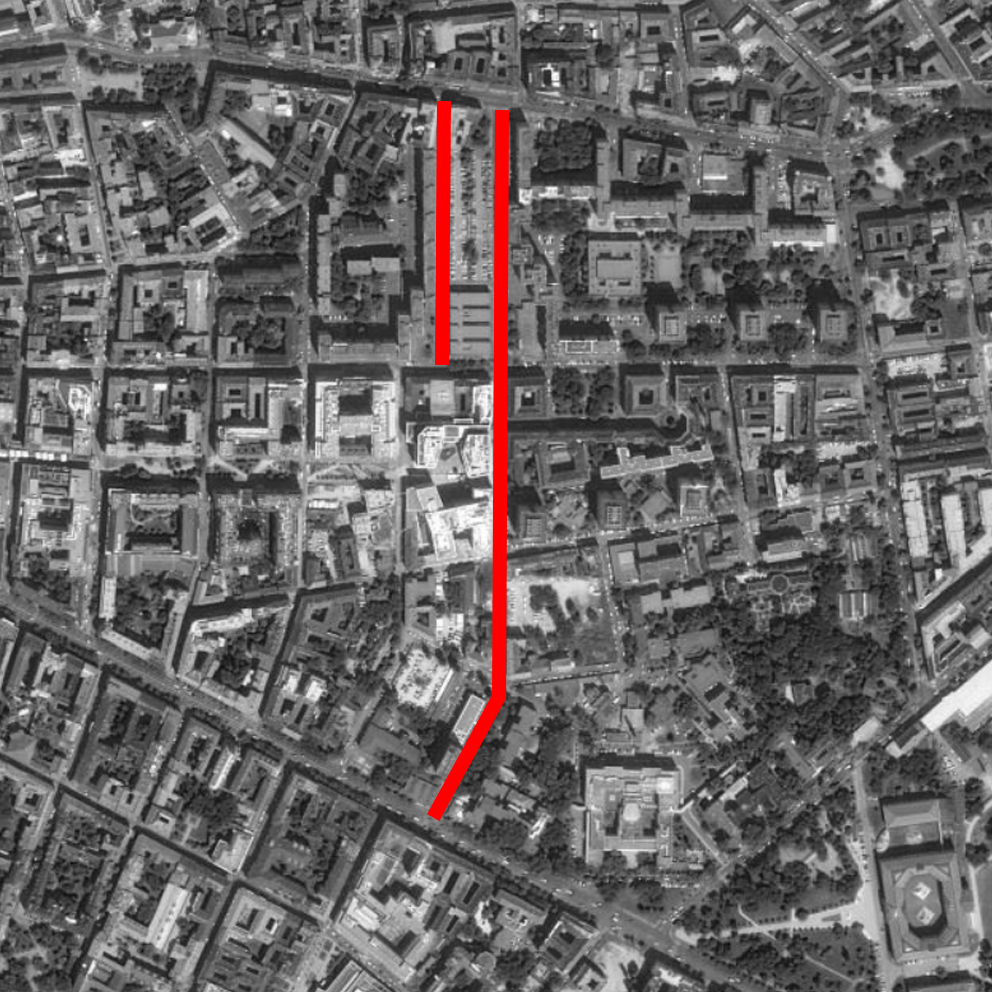

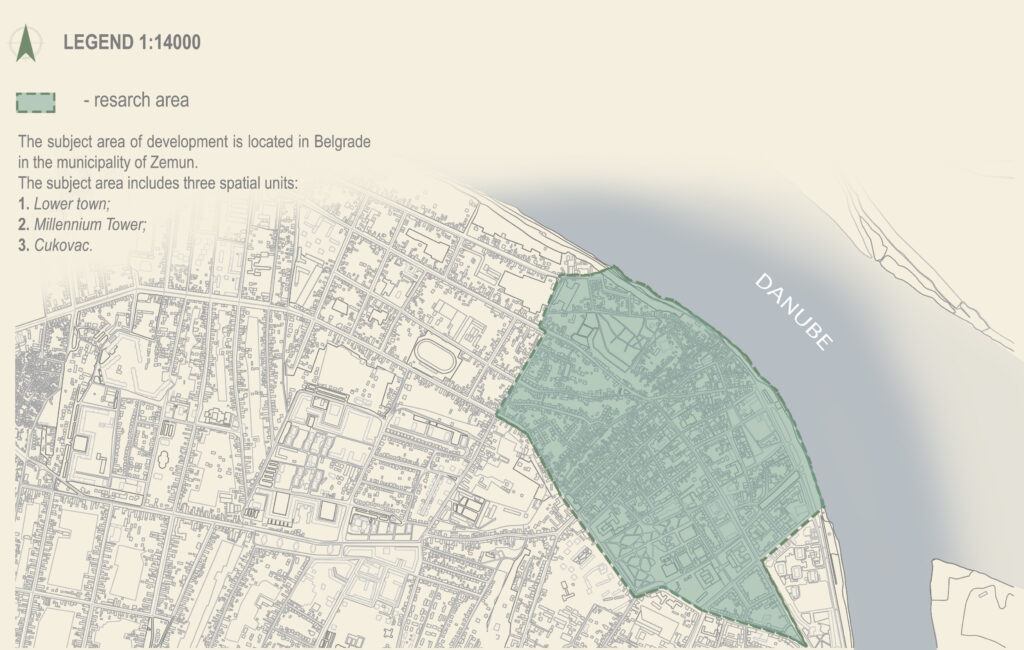

Site : Innere Stadt, between Schwedenplatz and Stephen’s church

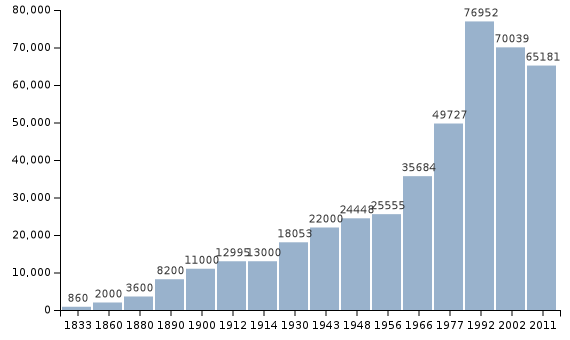

Today, more than 1.7 million people live in Vienna. Vienna is therefore not only the largest city in Austria but also the seventh largest city in the European Union.

The city is densely populated, as you would expect, this large city comes in with around 4,000 people per square kilometer. Therefore the density of Innere Stadt is higher then average with 5,572 people residing per square kilometer.

7 source : World population review, Vienna population 2020, https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/vienna-population

8 source : City population Website, Wien, https://www.citypopulation.de/en/austria/wiencity/901__innere_stadt/

Before 1850 the Innere Stadt was physically the equivalent of the city of Vienna today.

It concentrate most of the significant historic buildings such as Stephansdom or the Hofburg Imperial palace.

Before searching

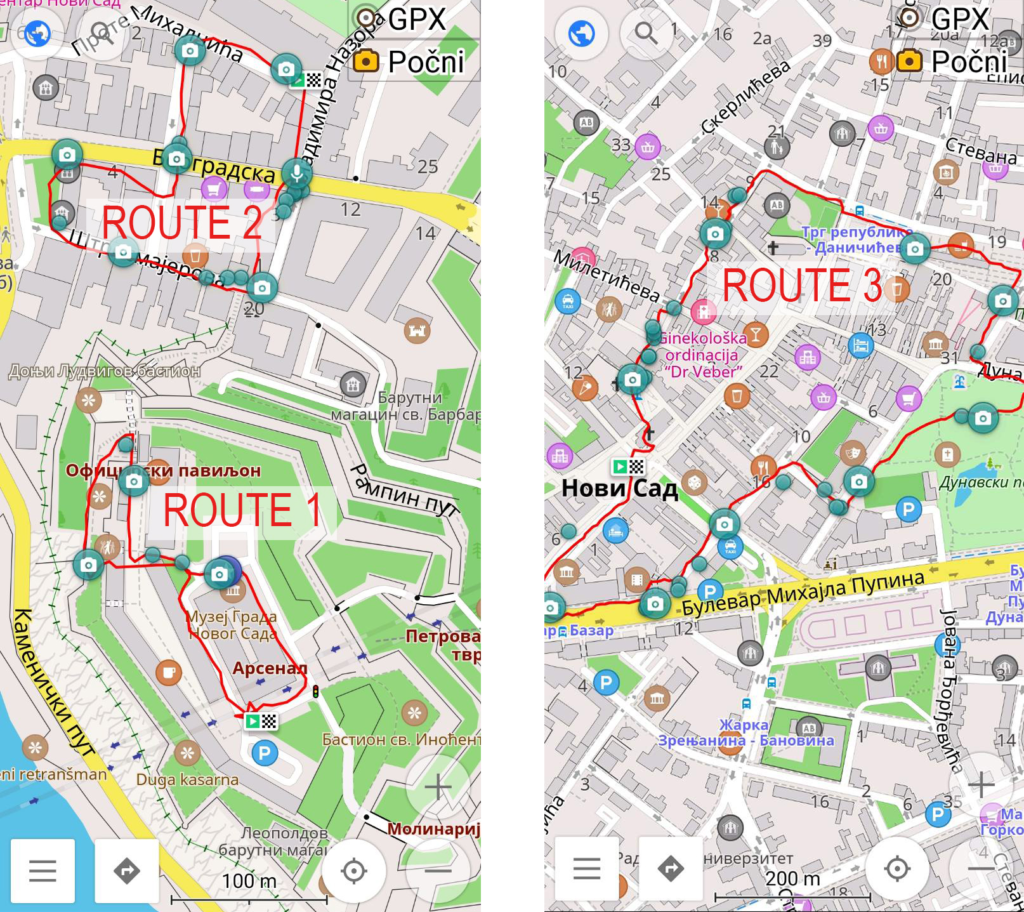

The plan for our searches was to come to the site the fist day to have a walk and take notes of our first impressions.

The second day we came back to make a tour with the osmand app and our phones to take some pictures.

The goal was to have a walk and trying to put ourserves in the shoes of a disabled/ elderly person. At every obstacles that we met we took a picture and added a marker. This is what made our track.

While searching

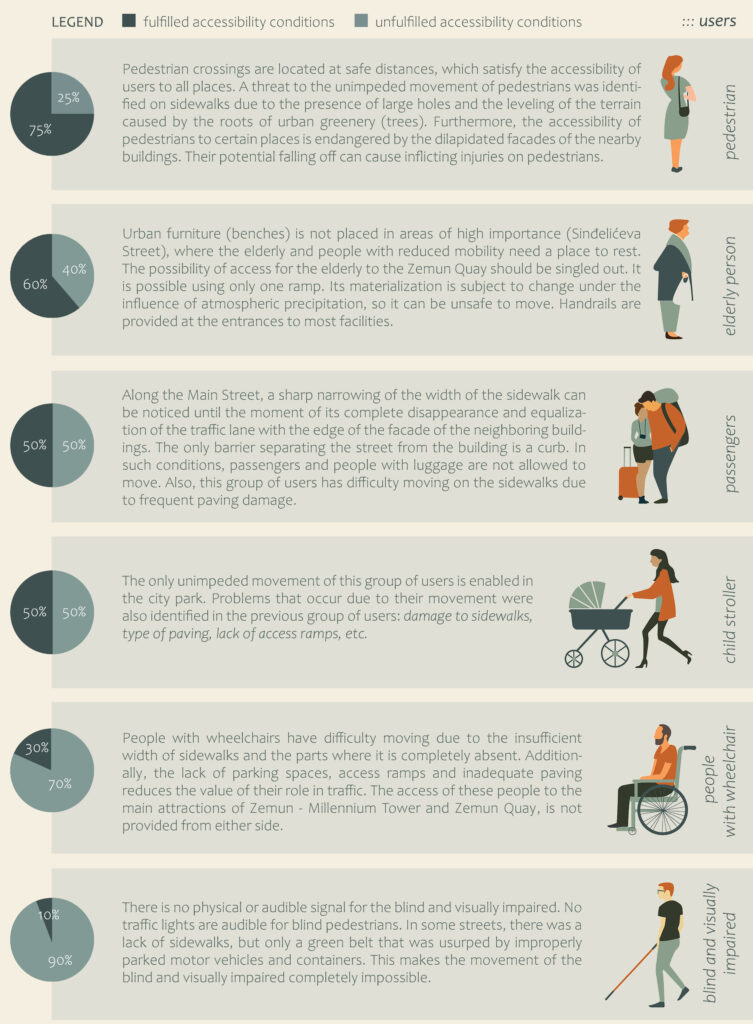

While visiting this place, we made a few statements. The center is mainly pedestrian. Therefore some cars can still access it ( for stores delivery, police etc.). There is not much parking places (and no disabled parking places) which makes it complicated to access for some people.

We also found this place quite ambiguous : in fact it is mainly pedestrian so there is no traffic light and crossing lines but some cars are still riding. This situation can be quite hard for blind people that cannot really know where cars run.

There is no maps of the city in braille as well.

Therefor there is a lot of urban furniture adapted to elederly and people with reduced mobility : a lot of chairs and bench on the sidewalks, lower ticket machine in the subway for people in wheelchairs, ramp in buses and tram and elevators to access the subway and larges sidewalks.

In fact Vienna is one of the most accessible capital in Europe.

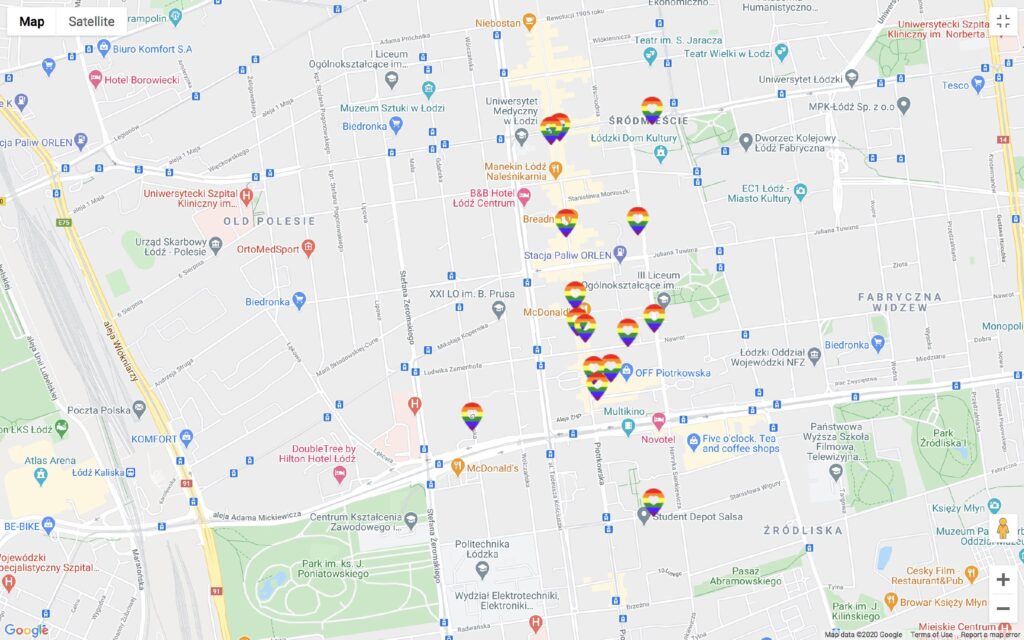

Accessibility map

About methodology

During our researches we decided to make one track together. Along the walk we took 25 pictures and added 25 markers.

During the walk we also took notes of the general aspects of the site we were studying and the recurrent obstacles. For exemple more then 60% of the stores that we saw had a step at the entrance so we could not add a marker for all those stores.

Difficulties

During this project we faced many difficulties.

The handling of the Osmand app was not very intuitive at first, but we got used to it quickly.

To pass the data obtained to GeoJSON we had to follow the instructions since this type of work was new for both of us, so we were a bit slow.

Once the data was in GeoJSON, we had to fix parts of the route and this process was very slow since there were many points, and in order to fix the problem we had to erase point by point which was very tedious.

As for adding the Pop Ups with images, it was a slow process in which we had to be very focus and in which we often had to fix details in the code.

OTHER SOURCES

- Wikipedia, Innere Stadt Wien , September 8th 2020 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Innere_Stadt

- Wikipedia, Districts of Vienna, September 8th 2020 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Districts_of_Vienna

- Wikipedia, European Union disability policy, August 11th 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union_disability_policy

- Stadt Wien Website, The years of the Allied Forces in Vienna (1945 to 1955) – History of Vienna, https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/overview/reconstruction.html

- Universität Wien Website, History of the disability movement in Austria, June 2018, https://lehrerinnenbildung.univie.ac.at/en/fields-of-work/inclusive-education/research-projects/current-projects/history-of-the-disability-movement-in-austria/

- World population review, Vienna population 2020, https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/vienna-population

- City population website, Wien, https://www.citypopulation.de/en/austria/wien/_/90001__wien/