Our research was recorded on one of the streets of Budapest, Szigony. The street is located on the edge of downtown. A really special, diverse street scene has emerged in recent decades because of this pherical situation. Along with the development of Hungary and the Budapest, this district has also changed a lot. This kind of development has had an impact on the built environment – the buildings and the streets have been replaced, yet the role and social stratum of the area in the city have not changed much. For the past hundred years, the street has functioned as a kind of melting axis – this area was most characterized by poverty. Over the years, this area has also been nicknamed: the ghetto. This kind of negative reputation allowed different ages to try to implement mega-projects here. Their goal has always been the same: rehabilitation and gentrification. Today’s investments are also putting these words on their banner.

In our research, we are looking for the answer to how easily the gates of houses built in this special space and social situation are easily accessible. How buildings of different ages do relate to the street – and thus to their social and spatial environment. What gates do we enter through a house? What gates do we enter the city through?

The Site

Morphological history – development of the area

Morphological history – development of the area

In the 18th century, there was only a small field on the site of the district, with one-storey houses, orchards and forests. The area fell outside the city border.

Source: Mapire

Source: Mapire

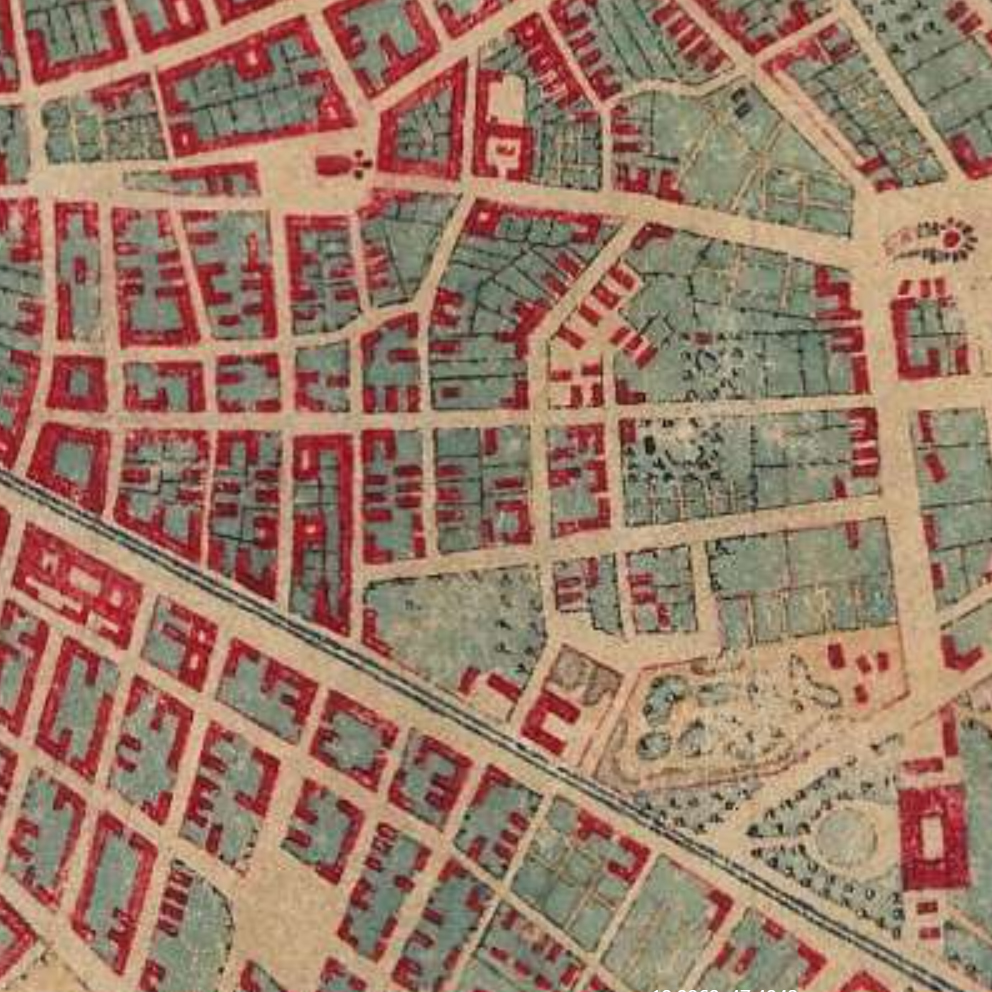

By the 19th century, the area was built. In addition to multi-storey apartment buildings, one-storey houses and large gardens and parks were also typical. Most of the workers from the countryside lived here, so the quality of the buildings is objectionable

Source: Mapire

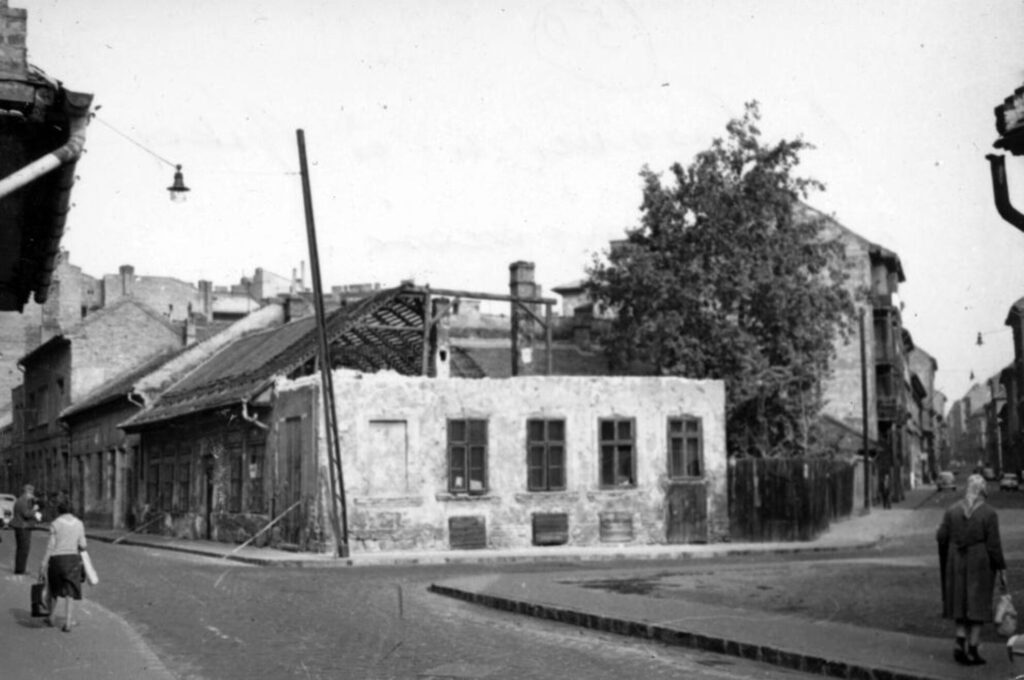

Due to the Second World War, the area got into a difficult situation. Construction stopped and the neighborhood retained its semi-urban atmosphere. The condition of the buildings began to deteriorate rapidly. Increasingly poorer strata moved in here. There was a crisis throughout the country – but the already more vulnerable areas were more severely affected by the crisis. This is also true of Budapest’s most infamous district – the 8th district. Within that the Corvin district, the Ghetto.

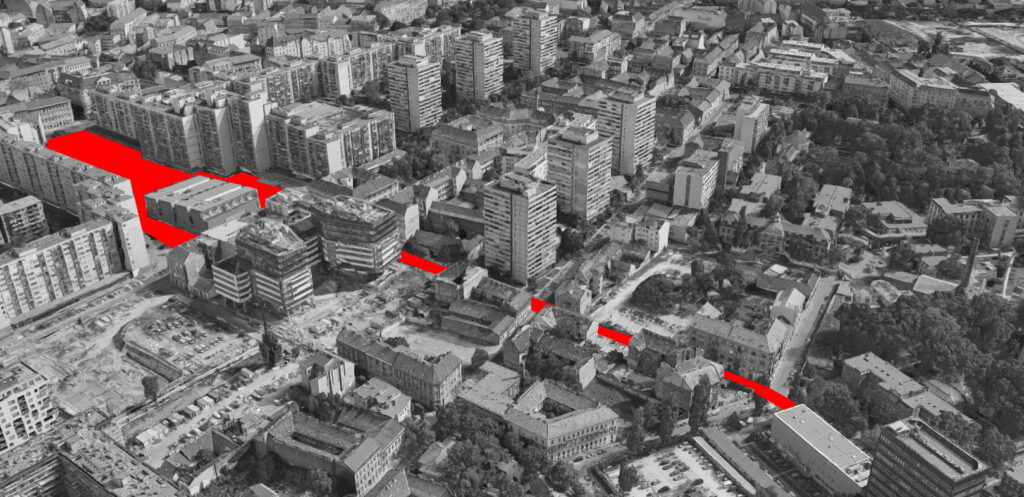

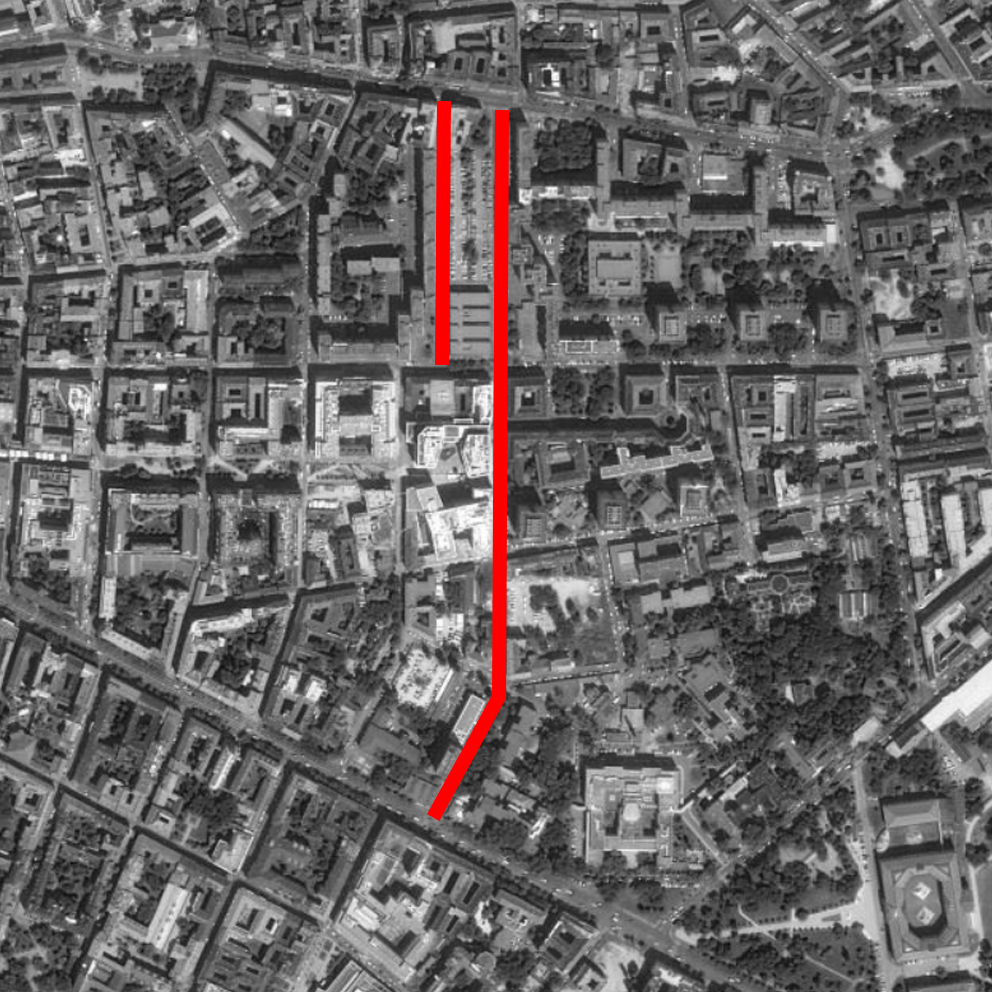

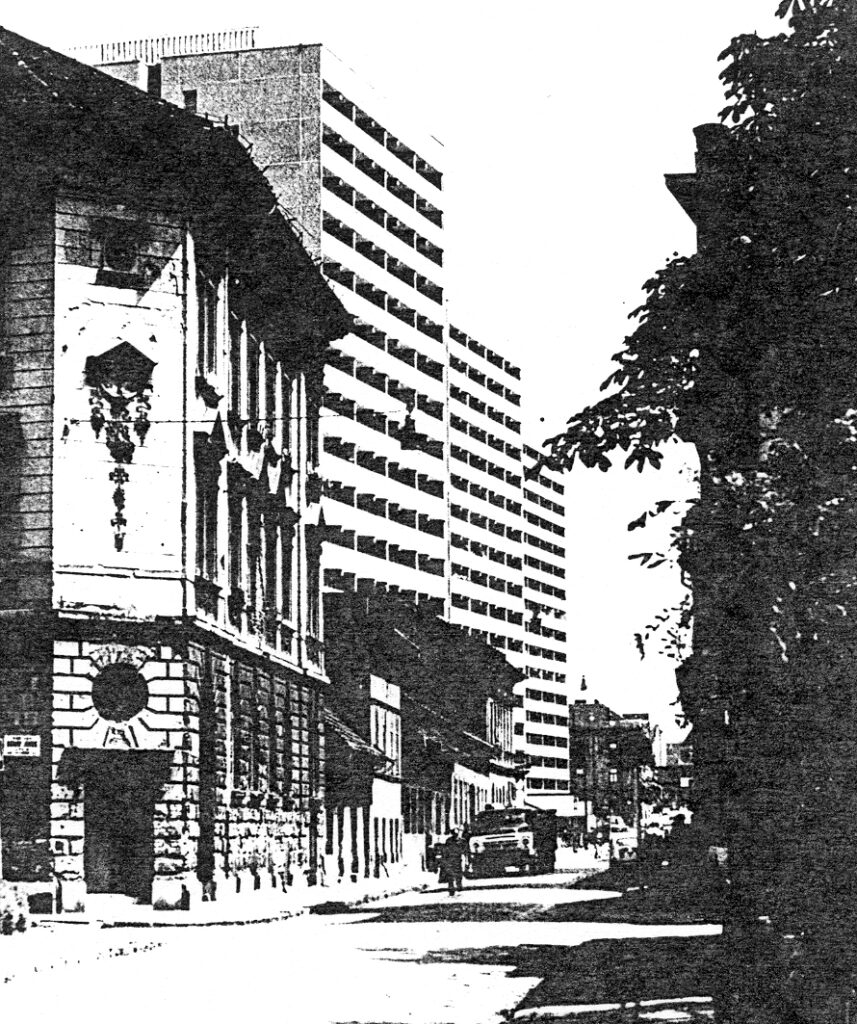

As you can see in today’s aerial photo, huge constructions have taken place in the area over the last 50 years. This trend is also characteristic of today. Construction can be divided into two markedly different eras: dictatorship – socialism / democracy – capitalism.

Socialist architecture

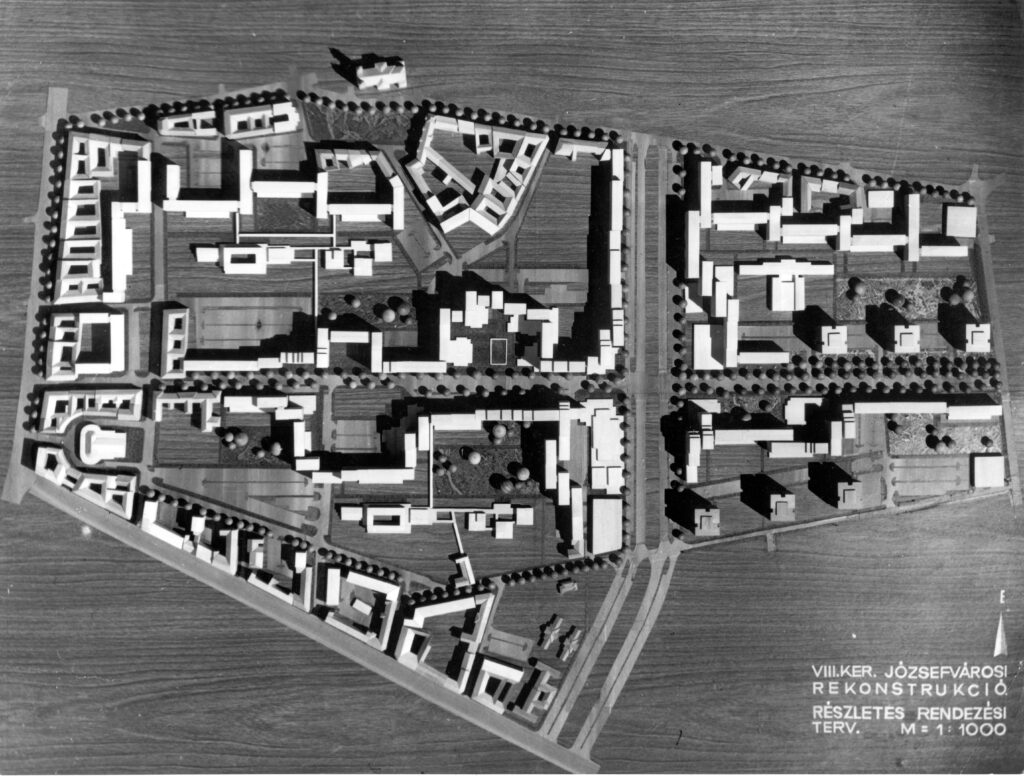

The first plan for the area was drawn up in 1962 and adopted a year later – this is in VIII. included the demolition of the southern parts of the district. In retrospect, it contained unrealistic expectations, with the demolition of 5,800 homes and the construction of 8,200 new homes planned under the second and third five-year plans in the area. In the early 60’s, houses built with traditional technology were designed, the model of the future construction would have been the József Attila housing estate. But the technical, economic, and political changes that took place over the decade (the commissioning of house factories, a new economic mechanism in 68) have significantly modified previous ideas. (Source: https://welovebudapest.com/cikk/2020/4/6/volt-egyszer-egy-nyolcker-50-eve-volt-a-tomo-utcai-toronyhaz-botranyos-atadasa-15-eve-epul-a-corvin-negyed)

Capitalist architecture

Perhaps the greatest and most controversial rehabilitation of the 21st century in Budapest has taken place in this area, The Corvin Quarter Project. Many refer to this as violent urban rehabilitation. A new luxury shopping street was built on the site of the ghetto. Detached from its surroundings and the past, the investment – which operates as an island – has greatly gentrified its surroundings – and now the surrounding streets have been flooded with new interventions and new constructions. The starting point of the Corvin Promenade is the Grand Boulevard (Grand Ring), while the end point is the Szigony Street. This gives rise to spatial tensions (and we have known since Mies van der Rohe that spatial tensions can be traced back to social tensions).

The development of the area raises many questions. What is a good urban rehabilitation like? Is there rehabilitation without gentrification? Is there good gentrification at all? Are displaced people just an additional loss? Is the city for the people or are the people for the city? Can neglected, low-quality buildings be the value of a neighborhood? Is it a historical heritage? Or is it just mere romanticization? The market first?

Research Agenda

In our research, we are looking for the answer to how easily the gates of houses built in this special space and social situation are easily accessible. How buildings of different ages relate to the street – and thus to their social and spatial environment. Are they closed? Maybe they are open? What does the ground floor of a building serve? Your early social expectations, or your future and past at the same time?

During our research, we took photos of every gates that opens onto Szigony Street. These gates are the connection between the private and public space. The most obvious architectural depiction of their relationship.

Photo: Benkő Melinda

Results

Examining the buildings we can divided them into 4 different 4 groups.

– architecture of historical ages (before Second World War.)

The ground floor strip of the buildings is well divided – there are cellar passages, windows, shops and entrance doors. Due to this kind of classic façade design, the buildings are aesthetically open to the street, this is their main façade. But in detail, you can’t always achieve that openness – it often has stairs, low or even narrow doors, all of which make your way difficult.

– socialist modern architecture

The ground floor lane is very different from the facade and floor plan of the other levels of the building. This often results in openness – such as in the case of a pharmacy, local government office, or even a supermarket. In this case, the ground floor opens almost completely and is decorated with ribbon windows. This kind of aesthetic openness is also consistent with functional openness – the interior is easily accessible to older people and people with reduced mobility. But if no public function is planned for the ground floor, the facades will become closed, brittle and monotonous. The doors to the stairwells have often been lifted off the ground by a stairs – a delicate gesture on the border of the private and public space on the one hand, and on the other hand they can make it terribly difficult for residents to get around.

– contemporary architecture

Representation is terribly important for contemporary buildings – at least in this area. Rich use of materials, interesting shapes and quality workmanship characterize these buildings. But looking at the entrances, a lot of doubt can arise in us. We can meet visually completely closed buildings (Pázmány Péter University) and visually open buildings (Nokia Headquarter). But given the number and position of the gates, we can conclude that they are functionally closed masses. They try to minimize the direct contact with the street.

Ease of access is a requirement for today’s buildings, but it is important to emphasize that this kind of entrances is often not part of the building’s organization, but only a mandatory, secondary element of it.

– temporary architecture

Due to their design, a barrier-free approach could be solved, yet they do not take advantage of this possibility. Although visually all of the temporary elements are open – as they settled here to serve the local market and society – they are not always easily accessible physically.

Conclusion

After examining the street, we can conclude that the architects do not sufficiently address the issue of accessibility. Many times, easy accessibility is only due to chance or laws. But architects does not treat this as an important part of design.

Description of methodology

To get to know the location, we walked into the area several times. Due to the exchange of views during the walk, we finally decided to deal with the ground floor of the buildings – especially the entrances. We decided to take photos for the most spectacular presentation. During this task, we took 104 pictures, which can be seen in the first map. We chose 22 pictures (equally from every architectural era) from them to show the essence of this research for the better acceptability. This can be seen in the second map.

The movement of people usually has a purpose – and that goal is very often an inside space. This means that one crosses a gate starting from home, then travels outdoors, until finally crossing a gate again — the entrance of one’s goal. We dealt with the starting and ending point of the traffic, the entrances. While this is a limited, narrow area of barrier-free design, as an architect perhaps it can be shaped most consciously. What’s more, because of its dramaturgy, it’s in a particularly spectacular position.

Methodological reflection

It is pretty sad that the workshop was not in Vienna – so it was difficult to focus on both the task and the lectures. Although the app was easily accessible to everyone, the placement of the points was inaccurate and the phone was quickly drained. As an inexperienced wordpress user, it was difficult to insert direct maps, although we were able to easily record multimedia recordings at that location.

Overall, we will continue our research. For us, a different examination of the neighborhood and the buildings would be relevant (floor plan, facades, social strata, etc.) after these, in the future.

Authors: Bence Bene, Adam Pirity

Consultant: Melinda Benkő